Guiding Principles for Wellbeing from both UKSAR and ICAR

UKSAR and ICAR have both produced guidance for teams and team members in looking after the wellbeing of their team members. These two articles summarise the full documents.

From the archives: Mountain Rescue Magazine Issue 93, July 2025.

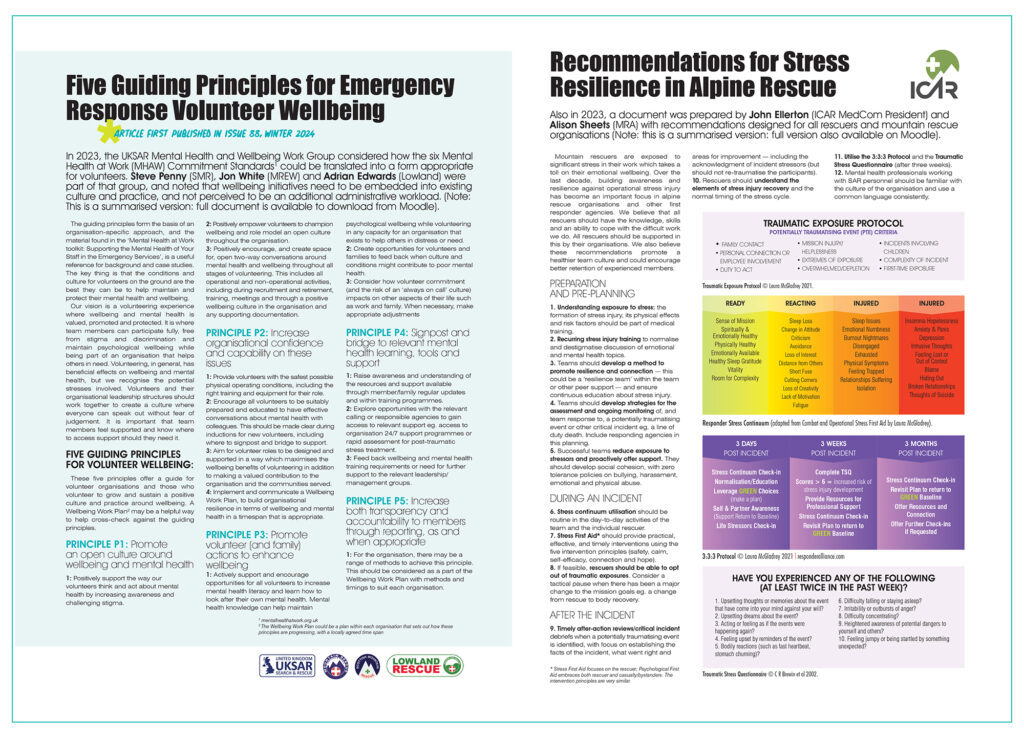

Five Guiding Principles for Emergency Response Volunteer Wellbeing

In 2023, the UKSAR Mental Health and Wellbeing Work Group considered how the six Mental Health at Work (MHAW) Commitment Standards could be translated into a form appropriate for volunteers. Steve Penny (Scottish Mountain Rescue), Jon White (Mountain Rescue England and Wales) and Adrian Edwards (Lowland Rescue) were part of that group, and noted that wellbeing initiatives need to be embedded into existing culture and practice, and not perceived to be an additional administrative workload. (Note: This is a summarised version).

The guiding principles form the basis of an organisation-specific approach, and the material found in the ‘Mental Health at Work toolkit: Supporting the Mental Health of Your Staff in the Emergency Services’, is a useful reference for background and case studies. The key thing is that the conditions and culture for volunteers on the ground are the best they can be to help maintain and protect their mental health and wellbeing.

Our vision is a volunteering experience where wellbeing and mental health is valued, promoted and protected. It is where team members can participate fully, free from stigma and discrimination and maintain psychological wellbeing while being part of an organisation that helps others in need. Volunteering, in general, has beneficial effects on wellbeing and mental health, but we recognise the potential stresses involved. Volunteers and their organisational leadership structures should work together to create a culture where everyone can speak out without fear of judgement. It is important that team members feel supported and know where to access support should they need it.

Five guiding principles for volunteer wellbeing:

These five principles offer a guide for volunteer organisations and those who volunteer to grow and sustain a positive culture and practice around wellbeing. A Wellbeing Work Plan2 may be a helpful way to help cross-check against the guiding principles.

Principle P1: Promote an open culture around wellbeing and mental health

1: Positively support the way our volunteers think and act about mental health by increasing awareness and challenging stigma.

2: Positively empower volunteers to champion wellbeing and role model an open culture throughout the organisation.

3: Positively encourage, and create space for, open two-way conversations around mental health and wellbeing throughout all stages of volunteering. This includes all operational and non-operational activities, including during recruitment and retirement, training, meetings and through a positive wellbeing culture in the organisation and any supporting documentation.

Principle P2: Increase organisational confidence and capability on these issues

1: Provide volunteers with the safest possible physical operating conditions, including the right training and equipment for their role.

2: Encourage all volunteers to be suitably prepared and educated to have effective conversations about mental health with colleagues. This should be made clear during inductions for new volunteers, including where to signpost and bridge to support.

3: Aim for volunteer roles to be designed and supported in a way which maximises the wellbeing benefits of volunteering in addition to making a valued contribution to the organisation and the communities served.

4: Implement and communicate a Wellbeing Work Plan, to build organisational resilience in terms of wellbeing and mental health in a timespan that is appropriate.

Principle P3: Promote volunteer (and family) actions to enhance wellbeing

1: Actively support and encourage opportunities for all volunteers to increase mental health literacy and learn how to look after their own mental health. Mental health knowledge can help maintain. psychological wellbeing while volunteering in any capacity for an organisation that exists to help others in distress or need.

2: Create opportunities for volunteers and families to feed back when culture and conditions might contribute to poor mental health.

3: Consider how volunteer commitment (and the risk of an ‘always on call’ culture) impacts on other aspects of their life such as work and family. When necessary, make appropriate adjustments

Principle P4: Signpost and bridge to relevant mental health learning, tools and support

1: Raise awareness and understanding of the resources and support available through member/family regular updates and within training programmes.

2: Explore opportunities with the relevant calling or responsible agencies to gain access to relevant support eg. access to organisation 24/7 support programmes or rapid assessment for post-traumatic stress treatment.

3: Feed back wellbeing and mental health training requirements or need for further support to the relevant leadership/ management groups.

Principle P5: Increase both transparency and accountability to members through reporting, as and when appropriate

1: For the organisation, there may be a range of methods to achieve this principle. This should be considered as a part of the Wellbeing Work Plan with methods and timings to suit each organisation.

Recommendations for Stress Resilience in Alpine Rescue

Also in 2023, a document was prepared by John Ellerton (ICAR MedCom President) and Alison Sheets (Mountain Rescue Ireland) with recommendations designed for all rescuers and mountain rescue organisations (Note: this is a summarised version).

Mountain rescuers are exposed to significant stress in their work which takes a toll on their emotional wellbeing. Over the last decade, building awareness and resilience against operational stress injury has become an important focus in alpine rescue organisations and other first responder agencies. We believe that all rescuers should have the knowledge, skills and an ability to cope with the difficult work we do. All rescuers should be supported in this by their organisations. We also believe these recommendations promote a healthier team culture and could encourage better retention of experienced members.

Preparation and pre-planning

1. Understanding exposure to stress: the formation of stress injury, its physical effects and risk factors should be part of medical training.

2. Recurring stress injury training to normalise and destigmatise discussion of emotional and mental health topics.

3. Teams should develop a method to promote resilience and connection — this could be a ‘resilience team’ within the team or other peer support — and ensure continuous education about stress injury.

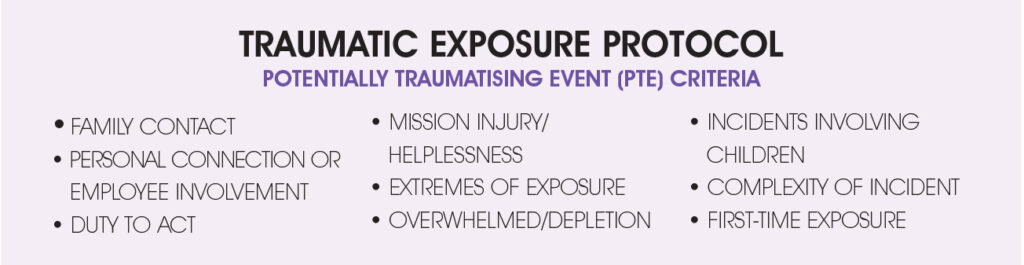

4. Teams should develop strategies for the assessment and ongoing monitoring of, and team response to, a potentially traumatising event or other critical incident eg. a line of duty death. Include responding agencies in this planning.

5. Successful teams reduce exposure to stressors and proactively offer support. They should develop social cohesion, with zero tolerance policies on bullying, harassment, emotional and physical abuse.

During an incident

6. Stress continuum utilisation should be routine in the day-to-day activities of the team and the individual rescuer.

7. Stress First Aid* should provide practical, effective and timely interventions using the five intervention principles (safety, calm, self-efficacy, connection and hope).

8. If feasible, rescuers should be able to opt out of traumatic exposures. Consider a tactical pause when there has been a major change to the mission goals eg. a change from rescue to body recovery.

After the incident

9. Timely after-action reviews/critical incident debriefs when a potentially traumatising event is identified, with focus on establishing the facts of the incident, what went right and areas for improvement — including the acknowledgment of incident stressors (but should not re-traumatise the participants).

10. Rescuers should understand the elements of stress injury recovery and the normal timing of the stress cycle.

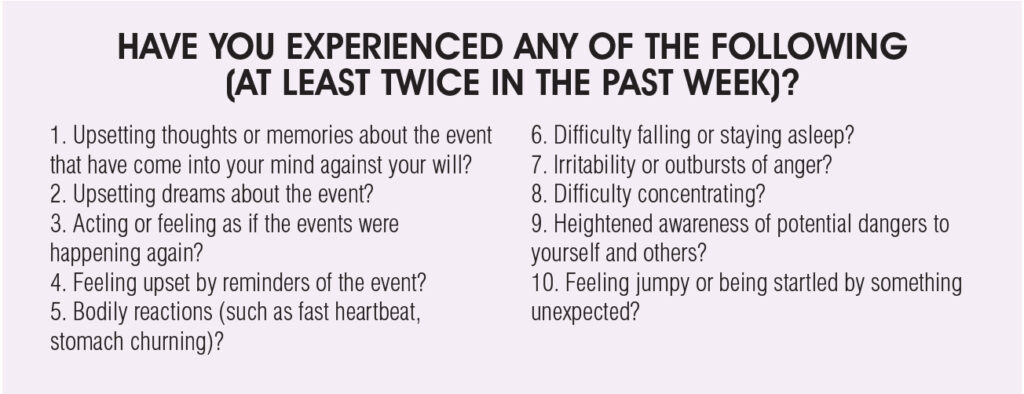

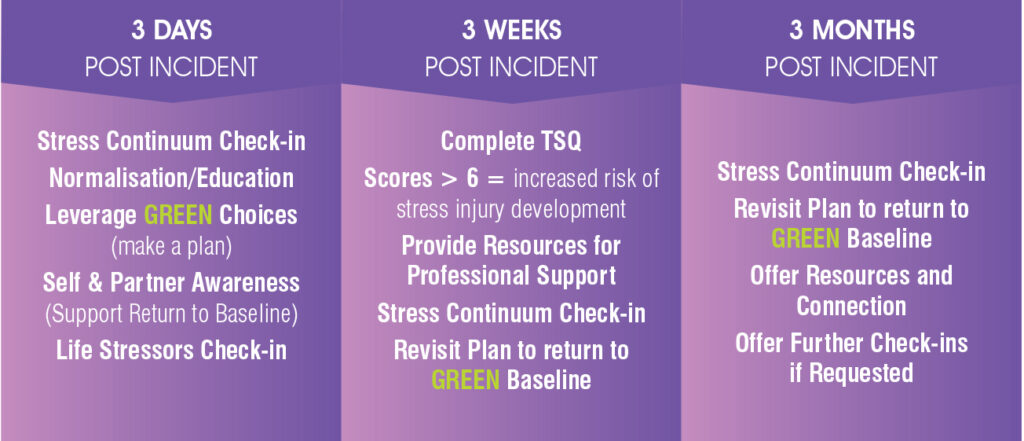

11. Utilise the 3:3:3 Protocol and the Traumatic Stress Questionnaire (after three weeks).

12. Mental health professionals working with SAR personnel should be familiar with the culture of the organisation and use a common language consistently.