Resilience: The Avalanche

Scottish Mountain Rescue Wellbeing Officer tells his personal story of dealing with a traumatic event, several years after the actual incident, during the winter of 1995.

From the archive: Mountain Rescue Magazine, Issue 70, October 2019.

The winter of 1995 was described by Blyth Wright as The Black Winter in his book A Chance in a Million?1. I was a newly qualified dog handler in SARDA and was called out to help search for a missing lone walker. At the time, there had been a considerable amount of snow but the weather had changed and slopes had become very unstable.

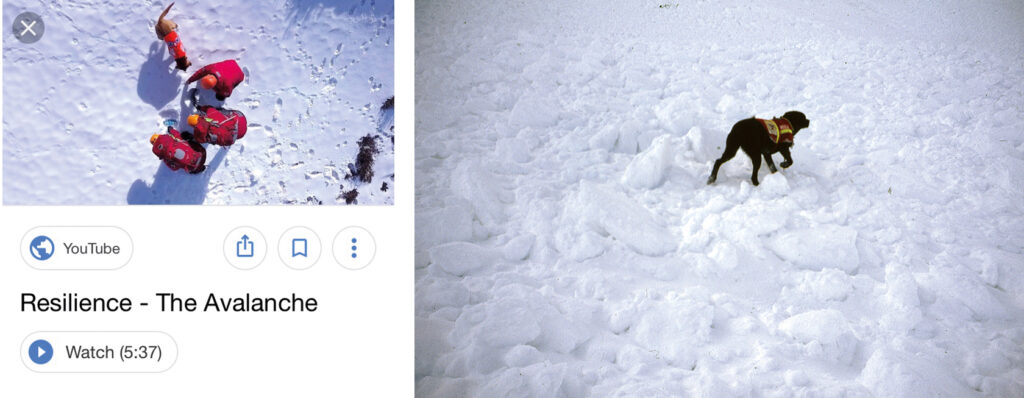

I was searching areas along with two other dog handlers when we came onto a huge avalanche (about 500m crown wall). We agreed we would spread out and move over the area from one side to another. I was in the middle and, within a matter of minutes, Tarah was digging in the snow and coming back to indicate. She had located the body of the missing walker buried beneath the avalanche debris. What I experienced in the hours and days following that incident were things I had not had to deal with previously.

This story is also found in the book Mountain Rescue2 by Bob Sharp and Judy Whiteside.

In this article, I will try to explain the reasons why it took almost 25 years to speak out openly and publicly (via social media channels) about an event that had a profound impact on me in my early years of mountain rescue, and why being comfortable to speak out and normalising such conversations is so important for us, not least to help break down the stigma often associated with our mental health in general.

First of all, why did I choose to speak out in a short film?

The answer to that one is quite straightforward. In March 2018, Scottish Mountain Rescue was approached by a newly qualified doctor, Matt Walton. Matt explained that he had made a film about his experiences of dealing with a traumatic call-out when on placement with the air ambulance in England and this had been received well. He was keen to make a second film relating to an avalanche incident, exploring the potential reactions to dealing with that from a volunteer responder perspective. However, he was based in Newcastle and needed to do any filming within the following week — and this included trying to film outside as well as an interview. As it happened, the story of my experience of finding a buried casualty with my search dog Tarah, and the impact that had on me, fitted the bill. In addition, I was only an hour from Newcastle and we still had some snow on the ground following ‘The Beast from the East’!

The answer to the second question — why did it take almost 25 years to speak out openly and publicly? — is trickier.

In the film, I describe the reactions I had in the hours and days following that call-out and the fact that at that time we had never been trained in these issues, so the reactions were confusing and worrying. I do remember it was important to be clear in my mind that I had done everything I could have done and was reassured to learn we could not have done more. I took no further action at the time.

Over the last 25 years I have had to deal with many incidents that have involved dealing with death and a few that have been high risk. Some of these have had a minimal impact on me but some have had much greater impact. And for others in the team this will have been the same — but not necessarily in relation to the same incidents. This is why incidents can be described as ‘potentially traumatic’ for an individual — we won’t all react to the same incident in the same way. It could be that we then don’t speak out if we feel we might be the only one experiencing effects when everyone else seems to be OK.

More recently, a couple of years ago, I had to deal with an issue in my personal life that seriously challenged my mental health. After years of dealing with potentially traumatic events in mountain rescue I knew I would benefit from help and yet I could not bring myself to seek that help. I know this is not uncommon in those of us who focus on helping others! Two things happened that changed my position.

The first was that I made an appointment with my GP in relation to physical symptoms that were becoming difficult to ignore and he quickly understood that there was more to this. The second was listening to an interview with someone who had taken years to ask for help and their turning point was that feeling well (or unwell) is not a competition. How many times do we all say to ourselves — why should I be feeling bad, so-and-so is in a far worse position? The truth is that we all have a right to be safe and well — it’s not a competition with others. So, having spoken out and reached out, I started to receive the help and support I needed.

It’s ok to talk!

And this explains why I chose to speak out now about my own experiences. It has been shown that stigma is a barrier to us speaking out — that might be self-stigma (our own willingness to verbalise the issues); institutional stigma (the culture and/ or barriers within an organisation or team); and public stigma (how do the public at large and/or media react). Featuring in the film gave me an opportunity to show to others, using a personal experience, that taking the step to speak out is incredibly valuable — it’s OK to talk! It was an opportunity to help normalise such conversations. Often, just having a listening ear from someone you trust can make all the difference and may be all you need.

The film was launched at the Emergency Services Show in September 2018 and circulated via various Twitter and Facebook accounts and was commented on by Stephen Fry who said, ‘Understand how trauma affects our emergency service personnel by watching this incredibly moving and important film’.

Speaking out in the film strengthened my resolve to support other mountain rescue volunteers to stay safe and stay well — #staysafestaywell — and to challenge barriers caused by stigma in its various guises. It is largely the reason I have been actively involved in the work of the UKSAR Wellbeing Group and development of the Wellbeing Framework, as well as a range of initiatives in my role as Wellbeing Officer for Scottish Mountain Rescue.

I hope you can find five minutes to watch the film — you can now find it on Lifelines Scotland and I hope you might find it of interest and use. If it helps just one person, it was worth speaking out publicly about my experiences — even if it took almost 25 years!

References: 1Bob Barton & Blyth Wright, 2000, ISBN 0-907521-59-2; 2Bob Sharp and Judy Whiteside, 2005, ISBN 1-904524-39-7